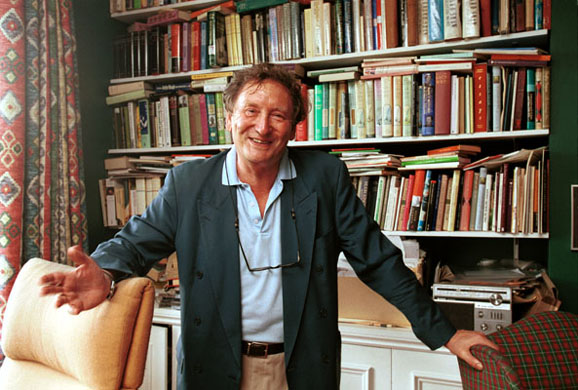

Thinking back to the early 1960s, Bertrand Russell, the subject of another prize winning biography by Ray Monk, was frequently seen on black and white television declaring his concerns over Nuclear Weapons. He stated, Neither a man nor a crowd nor a nation can be trusted to act humanely or to think sanely under the influence of a great fear. For nearly seventy years, mankind has wondered in the words of Sting, How can I save my boy from Oppenheimer’s deadly toy? As concerns about nuclear proliferation in relation to Iraq, Pakistan and North Korea escalate it is salutary to return to a thorough biography of the man, known as the father of the bomb, that felt a deep and urgent need to be at the centre and to belong, J Robert Oppenheimer.

Oppenheimer’s father, Julius, a wealthy cloth merchant came from Hesse and was among the many German Jews to arrive in America in 1888. Oppenheimer visited his Grandfather’s home at the age of four and thought it a medieval village. A strength of Monk’s biography is his facility in evoking locations. In adolescence Oppenheimer was attracted to New Mexico where he had been taken by his English teacher, Herbert Winslow Smith, and fell in love with horse riding and the landscape. At Cambridge, however, he was particularly miserable and suffered a nervous breakdown following his attempt to poison his elegant supervisor, P M S Blackett. His recovery on Corsica was due apparently to a passage from Proust, providing much needed stoic calm before his exciting time at the beautiful university and centre of theoretical physics in Göttingen.

The portrait emerging from letters and documents that Prof Monk has so carefully sifted, is of a highly intelligent man who assumes a debonair persona, motivating others, well-read and proficient in several languages from classical Greek to Sanskrit. His interest in physics covered the chemical bond to astrophysics, from quantum electrodynamics to cosmic rays. In all these fields he made major contributions. He even discovered the possibility of black holes. Here is a man that bullies and inspires his research students and whose lectures are displays of his own facility spiced with a high degree of arrogance and hauteur at the cost of clarity to his audience. Impatient and incompetent with arithmetical calculations, he was ham fisted with experiments. Oppenheimer, a tragic figure with a highly developed knowledge of classical tragedy lacked a real sense of self.

Monk’s biography is particularly good at clearly explaining basic physics. Especially the confusions between different formations of quantum mechanics, the difference between the absorption of neutrons in various isotopes of Uranium and the confusion between weak and strong nuclear forces in cosmic ray showers. This was an extremely exciting time in physics and the eloquence of this multi-layered biography lies in painting in both the political background and the personalities of Oppenheimer’s associates, friends, family and lovers.

This variety keeps the reader engaged throughout, iIn particular with the insight which Inside the Centre affords into American values and attitudes. Racism and anti-Semitism was deeply ingrained both in social and academic circles, notably at Harvard where he had been a student. Oppenheimer’s great contribution was the establishment of Berkley in California as a vital international centre for theoretical physics. Becoming a worthy American citizen was always a central concern to him. Seeing a fairer society was important to Oppenheimer who had actively supported a docker’s strike. This would land him in deep trouble with the FBI and later with the McCarthy inquisition and despite his endeavours at Los Alamos, his security clearance was withdrawn.

There is a sense of drama in this book which keeps the reader involved. This is due to the historically momentous events involved but enlivened by the personalities Oppenheimer encountered. His radical brother Frank was an able experimenter. There is the bulky, garrulous and memorable figure of the Swiss, Wolfgang Pauli, depicted among the thirty photographs with Oppenheimer in a boat on Lake Zurich and Ernest Lawrence obsessed with building larger and larger cyclotrons, using ersatz equipment like an 80 ton magnet rusting after WW1 in a junkyard. The contribution of one woman, a pacifist, Lisa Meitner, exiled in Sweden, together with that of Otto Hahn on Christmas Eve 1938 explaining nuclear fission and the devastating amount of energy released clarified the possibility of the construction of a weapon.

Monk’s technique when detailing a particular event or person, allows that the reader may see it differently. The detailed footnotes and comprehensive biography makes it possible to follow up alternative explanations. This is particularly useful in relation to a conflicted individual such as Oppenheimer who felt ambivalent about many issues, some of which he must have kept very close to his chest. There is a certain liberal generosity about Monk’s technique. This is a very fine intellectual biography.

An interview with Oppenheimer at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lVCL3Rnr8xE