Wandering down Chapel Street in Penzance, you cannot fail to recognise that you have entered that part of town where history feels close-by. The sea in the distance, the church and the chapel architecture is impressive, the Turk’s Head Tavern and the baroque wonder of the Egyptian House, the Portuguese consulate and almost opposite the house where George Eliot stayed waiting for calm weather for her voyage to the Scillies. Reading Melissa’s book is like taking a similar peregrination through lost corridors of time to recover a sense of the rich liveliness of Penwith’s past. Welcome to the psychogeography of Bronte’s Territories.

The Brontes are still much in the news. The Irish Times, just two weeks ago, were reporting on the O.U.P. computer analysis of Wuthering Heights apparently confirming it to be the work of Emily and not, as had been suggested, that of her brother Branwell. Iconoclasm may be in vogue. However, a square in Brussels – the city where two of the Bronte sisters studied French – is to be named in honour of the literary siblings. Other authors make claim to curious events in Shropshire in the early years of the 19th century drew the parents of genius together. It is to the intellectual and feminine furore of Penzance and its inspiring hinterland that Hardie’s work appropriately returns us.

In a key chapter on the literature and legend of Cornwall from 1760 much mention is made of the intriguing and taciturn figure of Joseph Carne, a geologist of great renown and an energetic banker. His personality was such that he combined a skill with numbers with a strong Methodist belief and mixed in a variety of literary circles. Nearby Falmouth was a key port for the Packet boats recorded in the poetry and memoirs of Byron and Southey. It too was the home of the Quaker family of Foxes who founded the Cornwall Polytechnic Society in 1832. Carne was a friend and shared their Non-Conformist beliefs. Hardie shows how Carne encouraged his daughter in her geological studies and mentions the doctors, engineers, vicars and scientists whose cultural sources were enriched by contacts which included Bretons, Huguenots, Hessians as well as a significant Jewish community. She reminds us that in reading Davy, for example, we encounter not just a socially beneficent scientist, a traveller and a poet. This is the endowment the Branwell sisters took to Haworth.

It is interesting to consider that within this Cornish background at this period there were a number of competing beliefs and attitudes. There were the mythical beliefs fostered from folklore- piskies and stories in the expiring Cornish language. There was the old religion of Rome not far beneath the surface. Yet there were also new discoveries especially in medicine and geology that fostered a scientific empiricism. This can be seen in figures such as Davies Gilbert to whom this book gives due prominence- a polymath, mathematician, engineer and President of the Royal Society and a wonderful diarist to boot. William Temple much later stated, “The Church exists primarily for the sake of those who are still outside it. It is a mistake to suppose that God is only, or even chiefly, concerned with religion.” It was the evangelical zeal of the Wesley brothers and their belief in education, temperance combined with stunningly beautiful hymns. It was also a challenge to superstition. It is often said it averted revolution which France and later Peterloo portended.

Melissa Hardie shows us the other supportive factors that came into this heady mixture and sustained the Branwells and flowered in the Bronte’s work. These are twofold; the societies and the family or kinship links. The Penzance Ladies Reading group who carefully studied together a stunning variety of literature from the classics of the Ancients to the contemporary travel writings. Not forgetting the subversive eloquence of Lord Byron, a gentleman with Cornish links through the Trevanions. The founding of libraries and collection of artefacts had practical even economic benefits. The Royal Cornwall Geological Society studies into metallic intrusions assisted the efficiency of mining. Local banks provided the capital for further developments in the industry as well as the magnificent Wesleyan Chapels that the Carnes, Branwells and Battens founded and fostered.

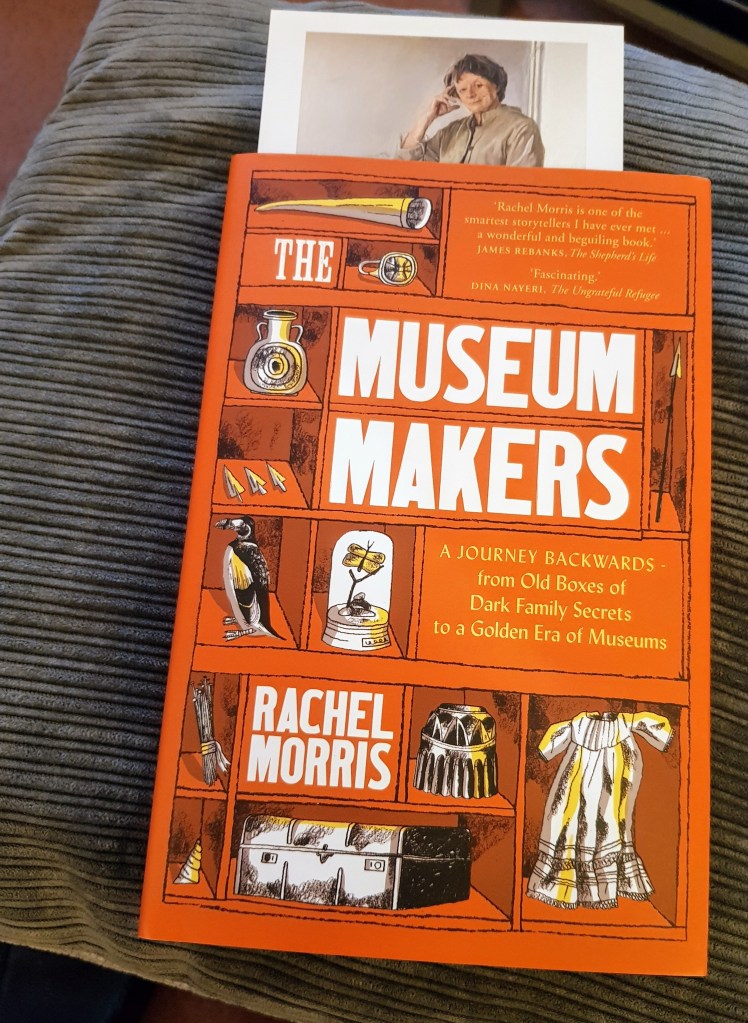

The author has researched both land and legacy extensively. Her approach is frequently imaginative and sometimes speculative. This is a strength because she is also at pains to inform the reader of the limitations of the evidence. Footnotes and suggested reading in themselves are useful but the illustrations are worthy of pondering- several works of art in themselves. They add significant detail. This patient work by Melissa supported by other members of the resplendent Hypatia Trust must be counted as filling a deep fissure, or as we might say in Cornwall, a zawn in Bronte Studies.

See also from the Guardian –

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/jun/29/bronte-grandfather-smuggling-past-financed-books-charlotte-emily-anne

Ruth Scurr has written an intriguing biography of Aubrey which has been reviewed by the Guardian

Ruth Scurr has written an intriguing biography of Aubrey which has been reviewed by the Guardian

![John Aubrey: My Own Life by [Scurr, Ruth]](https://images-eu.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51wZteLLLJL.jpg)